Our Photo

& Picture Gallery

Our Photo

& Picture Gallery

Good

photos of Swifts have until now been rare. But recent activities in

Swift study, especially by people with DIY colonies, combined with the

advent of the digital camera, have produced some great pictures. Here

are a few to whet your appetite! They show the amazing, daring, skilful

and exciting nature of these birds, as well as their overpowering charm.

Need photos of Swifts for environmental purposes? We may be able to help: click here to e-mail Swift

Conservation

|

An

amazing photograph of a Swift actually upside down in flight,

taken in June 2020 by Klaus Roggel in Berlin. Klaus tells us that: "On

the 3rd of June I managed to get a shot that shows a Swift in "reverse

flight". Exceptionally, it's eyes are not parallel with the horizon in

turning flight as is usually the case. You can always see how acrobatic the flight manoeuvres of the Swifts look, it is just so difficult to capture these moments with the camera. I was lucky and chance came to my side". It looks as though the Swift's thorax and wings are upside down, while the abdomen and tail are the right way up, and the head is on its side, looking down to the left. And it is doing all that while flying and turning at high speed, imposing great stresses onto all of its body and wings. What incredible birds they are! Photo © www.mauersegler.klausroggel.de 2020 |

|

A

fine photograph of Swifts in their nestboxes at Alain Georgy's home

Swift colony near La Chaux de Fonds in the Jura region of Switzerland. Alain has been making the very higest quality nestboxes for both Swifts and House Martins for many years now. He has equipped large colonies not only at his own home, but also at numerous buildings in the area where he lives, such as barns, a sawmill, a disused electricity substation, farm buidings and a special House Martin and Bat tower too. The photo shows Swifts in two of his distinctive nestboxes, together with behind them, a Swift using an enlarged type of House Martin nest box, something Alain invented and which they have taken to very happily indeed. Photo © Alain Georgy |

|

This

photograph shows a rare but spectacular phenomenon, "huddling" Swifts.

When Swifts on migration get caught out by cold and / or wet weather,

with no nest places to shelter in, and no flying insects to eat, they

may cling to any structure to rest and try to get out of the cold and

wet. Sometimes they do this alone, sometimes in large numbers, such as here on this window frame, where possibly as many as a hundred Swifts are clinging together, to try and keep warm. Often they fail, and are found dead on the ground the next day having perished from starvation and hypothermia. Indeed, it is thought that most Swift mortality comes from starvation and dehydration. We were sent this photo by someone who did not know who took it. We thought it valuable to show for educational purposes. If you took the photo, or know who did, please let us know as we are keen to credit and thank them. |

|

The "Scanish Swift", a fossil Swift from 49 million years ago and the oldest known Swift. (Scaniacypselus szarskii; Apodidae; Mayr & Peters 1999) This species measured about 80mm from head to tail, and had a wingspan of about 200mm, rather smaller than our modern Swift. It flew and hunted insects over the shallow tropical seas and marshlands in the area that is now Hesse in Germany. It died in flight, falling into the sea, and was preserved in the oil shales of the Grube Messel. You

can see this superb fossil in the Senckenberg Museum

in Frankfurt. Click

here

to see their web site and find out more. |

|

This excellent photo shows an adult Swift in level flight. |

|

|

A pair of Alpine Swifts, Apus

melba, migrating over the dusty hills outside

Tarifa in Andalusia, Southern Spain, heading for

Morrocco in Autumn 2014. |

|

|

This Little Swift, seen

over Andalusia in southern Spain, is just about

a European Species, with a few breeding outposts

in Southern Spain, but otherwise a sub-Mediterranean Old

World bird with a patchy range that takes it from

Africa right across to India and southern China.

It is everywhere rather dependent on urban

areas for nest sites, and at its most abundant in

sub-Saharan Africa and India, where it is a

common bird. |

|

|

Nothing

flies like a Swift! Speed, aerobatics, drama, social

interaction, hunting activity, flying for the joy

of it, that is what Swifts do, and what makes

them so magical. |

|

|

Look

at this one! The Swift is vertical in the air, on

its side, and its head is perfectly level with the

ground. |

|

|

They don't get

more dramatic than this! A fantastic photo of a

Swift skimming a dead calm water surface and just about to drink. Try flying like this

and not getting wet...... you would be very hard

put to do it! |

|

|

Returning to feed its chicks

with its throat stuffed with food, this excellent

photo shows how Swifts carry a "food ball" made up of hundreds of

small flying insects. |

|

|

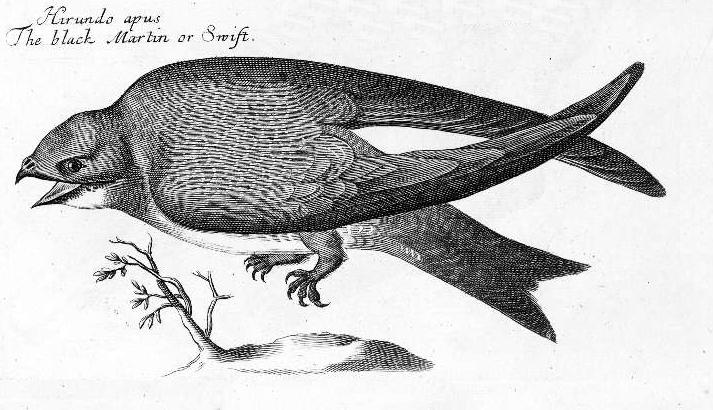

One of the first,

if not the first, accurate illustrations of a Swift,

prepared at the behest of the pioneering naturalist

Francis Willoughby, 1676. |

|

|

A

flock of screaming Swifts dashes past a wall in

Israel, marking their territory and strengthening

their bonds with their partners nesting in crevices

near by. In the Middle East Swifts start to arrive

and nest in February, and are gone by the end of

June. This early nesting period coincides with insect

availability and also with a cooler period; the

extreme heat of the summer would make nest places

too hot, cooking the eggs and killing the

chicks. |

|

|

This photo

shows an adult Swift in a typical, yet now fast-vanishing

nest place, the open eaves of an old building. |

|

|

An

immature Swift peeks out from its nest hole in a

tree. Note the very pale face, typical of juveniles. Photo © Olle Tenow |

|

|

Journey

to the Centre of the Earth! |

|

|

Swifts

nesting in a hole behind drainpipes in a suburban house. These

types of nest places are often stopped up during

renovation or redecoration work, and the Swifts

as a result lose their nestplaces for good. It is

this sort of well-meant but uninformed repair work

that is costing so many Swifts their nestplaces,

and even sometimes their lives as the chicks become

trapped in the nest holes and die. |

|

A new Swift chick sleeps beside its parent. If it survives, this will be the longest period of rest it ever knows. Most of the rest of its life will be spent on the wing. If lucky, it may live for 10 years, and in that time it will fly 20 times to and back from Southern Africa. The nest is basic, made from airborne debris, feathers, moss and saliva. Sometimes Swifts don't make a nest at all. They just lay the eggs on the bare surface. Swifts usually raise no more than 2 chicks, with a family of just

one being quite common. |

|

|

In

this spectacular image, Amir Ben Dov has captured

the moment when a Swift lines up with its target

snack, a large flying insect. It is thought they can tell the difference by the sound each creature makes when it flies. Photo © Amir Ben Dov |

|

|

|

|

A

Swift

displays its agility, immensely long wings

and also its pale chin (rarely visible from the

ground) as it flies up to its nest place in a building. |

|

|

This

young Swift was found exhausted and unable to fly

on Guernsey one summer. It was rescued by Margers

Martinsons and Nick Winship, nursed back to health by

the staff of the Guernsey Animal Shelter and released

to fly

off to Africa. |

|

|

Swifts can often find places to nest under ill-fitting pantiles on old roofs. These two photographs, taken near Lincoln, show a Swift, its throat bloated with insect food collected in the air for its chicks, returning to its nest place beneath the tiles. See how the Swift is using its entire body as an air-brake to stop its forward movement. It will have approached the nest at speed, and must decelerate rapidly to land safely. The body is held almost vertical, and the wings and tail are spread out to present as big an obstacle to the air as possible. New

or renovated pantile roofs are easily adapted to

let Swifts nest in them, without any fuss or mess.

See our Nest

Places in Pantile Roofs

page for more photos and details. |

|

|

This next photo shows the Swift landing. Forward movement is limited to settling on its outspread feet, as the tail is actually in contact with the tiles and will be slowing forward movement to nil. The Swift will now scuttle on its very short legs beneath the tiles to feed its young, then emerge very rapidly to take off and fetch more food. It

will continue to do this in a series of shuttle

flights for the 40 or so days it will take to rear

its chicks to the stage where they are perfectly

feathered, and can fly off straight to Southern

Africa for their first Winter. |

|

|

A

Swift meets its end as a meal for a young Yellow-legged Gull, on a

rooftop in Rome. Swifts have been nesting in Rome for maybe 2500 years.

The patterns of the tiles haven't changed since the days of the Romans;

they are perfect for Swifts to breed and roost under. Photo © Gerry Firth |

|

Two juvenile Swifts sit in their nest, almost ready to fly to Africa for the winter. Note the thin nest-lining of saliva and a few feathers (caught in flight) that make the man-made nest cup comfortable. Juvenile Swifts, like these, have a pale edge to the feathers of the head and wings, that wears away as they mature. Adults are all-dark, with a pale chin patch, difficult to see except in bright sunlight; they are much darker than the juveniles. Swifts can continue to use the same nest space for many years

precisely because, unlike other birds, they do not fill it up with

debris. |

|

|

This

photo shows fascinating details of the Swift's aerodynamic

features. Note the alulae or "bastard wings"

sticking up from the normal wing surface about a

quarter way out from the body. These are fully controllable

by the bird, corresponding to the "slots"

used on aircraft, and give increased lift and manoeuvrability

at low speeds. The tail is here dipped to the bird's

right, showing how it is steering through the air,

a bit like the rudder on a boat. |

|

|

An

amazingly dramatic photo of an enraged Swift driving

off a rival from his nest space after a bitter fight.

Swifts will compete and contest for nest spaces,

the more so if there is a shortage of them. Fights

can last for hours, the combatants lying gripped

and struggling in each others' claws, until one

gives up and succeeds in getting away. |

|

|

A

handsome photo of a Swift in flight, giving good

views of its underside and especially its chin and

tail. You can see the pale throat, often impossible

to see in normal light, and also the sculptured

effect of the tail and body boundary. |

|

|

Two

Swifts in flight - a more exhilarating and satisfying

sight is hard to imagine. The sheer beauty, skill,

daring and vigour of these birds as they dash across

the sky is just amazing. |

|

|

Swifts

have to drink, and they have to do it in flight

as they cannot land on the ground, unlike the Swallows

and Martins who can drink at the water's edge if

they need to. |

|

|

Contact!

The Swift is scooping up water at high speed, leaving

a white-water wake where its lower bill has cut

the surface. |

|

This fascinating photo shows a Pallid Swift ( a very similar species that breeds mostly around the Mediterranean) with a ball of captured insects in its throat; note the bulge. Swifts catch insects by pursuing and snatching, and when in swarms of small insects, by just scooping them up, like Basking Sharks catching plankton. The compressed insects are then carried to the nest and fed to the chicks. Swifts will travel immense distances to find food for their chicks.

Several years ago, when bad summer weather diminished insects

in Sweden, Swifts there moved en masse to Bavaria to gather

food. To cope with this, Swift chicks can endure several days without food by initiating a

torpid state where their body temperature and activity fall to

minimal levels. |

|

A sight that is getting rarer every year as rebuilding and refurbishment remove ever more nest places. A flock of Swifts renews its social and territorial links, in fast screaming flight above their nesting territory. Note the amazing flexibility of their wings. This gives them supreme control of the air, enabling Swifts to fly like no other bird, much faster, with greater agility and grace. Swifts display a variety of social flights, from low level screaming flight of the birds nesting in just one or two streets, to big late-summer get-togethers of the year-old non breeders from several colonies. These are flown at much higher levels at dusk, when they ascend to the heavens to sleep on the wing. Swifts sleep in flight with their senses of place, windspeed and

direction alert. Gliding on the breeze, they compensate for wind

drift and change of direction to stay in place above their home

territory. At dawn they descend rapidly back to lower levels, to fly

and feed around their familiar territory. |

|

A fine study of a Swift in flight. The forked tail is

rather

different from those of the Swallows and Martins with which the Swift,

while no relative, is often confused. |

|

Two alert young Swifts sit in their man-made nest box. |

|

Coming in low and fast, a feeding Swift chases invisible insects

during 2004's plethora of huge aphid swarms. |

|

|

|

|

Coming

in fast! A Pallid Swift does a rapid turn in the

air over Tarifa, Southern Spain. See how the tail

is dipped to act like a rudder, cutting the air

and forcing the bird into a turn. One wing is dipped

so the bird can pivot on it, while the

extended flat wing provides the lift that keeps

the bird in the air. The faster the bird flies,

the "tougher" the air will become, behaving

much like a liquid at the highest speeds. |

|

|

A

common but often overlooked habit of Swifts is to

fly up a building's walls to have a look for suitable

nest places, or, having established a nest, to visit

the nestplace to feed the chicks. |

|

|

Swifts mate in the air, or on the nest. Here you can see a spectacular coupling in flight. They are perhaps the only birds that do this, evidence of their amazing flying skills and their completely airborne life style. For Swifts, not flying is to be in danger, the air is the safest place they can be. This behaviour is easy enough to see, if you watch Swifts carefully on their high-in-the-sky flights early on in May and June. But the whole act takes only a second or two, so you have to be sharp eyed and sharp witted to witness it! Photo © Graham Catley |

|

This superb photo shows a pair of Pallid Swifts, the

lighter-coloured southern Swift species. They breed on the

Western Mediterranean littoral and along the Persian Gulf, and occasionally

turn up in the UK. Because of this they can spend longer in the breeding areas,

(from April to November in Southern France), and can raise two

broods. They like

rocky gorges and cliff faces as nest sites, preferring coastal or river valley

sites. |

|

A stunning study of a Pallid Swift, flying through a

town on the Persian Gulf. The lighter colour

of the bird, so evident here, is best seen in brilliant sunlight. |

|

|

Another fine photo of a Pallid Swift, seen here over Tarifa in Southern Spain. There are some slight visual differences apparent here differentiating it from the Common Swift. The bird appears broader winged and more plump. More

reliable clues are the paler

colour, (seen best in very bright sunlight or from

above) and the slightly deeper tone of their calls. |

|

This close up of a young Swift's head, several times larger than

life size, shows the unique scale-like feathering, and the

streamlined shape, supporting high-speed flight. |